From somewhere within Dante Alighieri’s Ninth Circle of Hell, encased far beneath the deepest strata of ice the Florentine bard carved especially for Judas Iscariot, the ghost of Ted Bundy has surfaced, merrily laughing. With the rating success of the true-crime docuseries Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, America’s preoccupation with the notorious serial killer has rekindled once more, enjoying a peculiar renaissance unseen since Anne Rule’s seminal book, The Stranger Beside Me, first hit the shelves nearly thirty-years ago. Where Mark Harmon originally starred as Ted in the television movie The Deliberate Stranger, Zac Efron assumed the lead for the latest iteration, Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, which premiered on Netflix last May.

America’s lust for true crime has never been greater. Ironically, female viewers—a demographic that would seemingly be most sensitive to the barrage of graphic crime scene photos and character re-enactments these programs routinely broadcast—are the targeted audience of this latest Bundy craze, and its greediest voyeurs. Monthly, it seems, the Hollywood sausage vat churns product culled from the same recycled batch of gristly trimmings. Allowing for chronological variation, most renditions begin with the same photo, a Ken Burns-effect monochromatic close-up of Bundy’s cocksure smirk as he preens for the cameras at his Florida trial, accompanied by a narrator’s ominous baritone. This somber introduction is usually followed in due course by exclusive interviews featuring several women, each shot in relief against an infinite black background, who claim they escaped Bundy’s clutches some forty years ago and lived to tell about it. There is grainy B-roll footage of his carnivalesque Florida electrocution in 1989, comprised of drunken frat boys, soaring roman candles, a bevy of idling news trucks, dour vigils, and opportunistic hucksters pawning miniature replicas of ‘Ol Sparky, the nickname of the oaken throne upon which the innards of the once cocksure former law student were boiled at dawn on January 24, 1989. Unshackled from the ethical bounds of attorney-client privilege, several of Bundy’s former lawyers appear in turn, promising to divulge never-before-heard tape recordings, delivering instead the same timeworn fare. Retired FBI profilers feed from the trough as well, offering stale talking points on serial killers and sexual deviants of similar ilk.

At some point along the storyboard’s predictable trajectory, these narratives inevitably revert to Bundy’s beginnings, a search for a starting point. Was he a genetic aberration? Perhaps his insatiable yearning to abduct and slaughter pretty young women arose at the moment he learned that his sister was actually his mother. Did he inherit his mutated chromosomal map through gardener Samuel Cowell, Ted’s allegedly abusive maternal grandfather, with whom he lived in Roxborough, Pennsylvania, until age four? Or did he acquire his genes from Jack Worthington, the father he never knew? During a pivotal moment in Conversations With a Killer, the camera zooms in upon a faded black and white snapshot of Ted as a smiling, towheaded little boy wearing a tank-top bathing suit on a crowded beach as he poses in the arms his mother, Louise. This picture appears to have been taken in Ocean City, New Jersey, for the Fourteenth Street Pier looms in the background, jutting out from the boardwalk promenade. Despite the prominent display of the photograph, the narrator never mentions where it was taken. Or that Bundy made numerous jaunts to the Jersey Shore when during his adolescence. Also left untold is any substantive discussion of the time he spent with his mother’s family in the Philadelphia suburb of Lafayette Hill, Pennsylvania, in 1969 while attending Temple University that winter and spring. His possible involvement in the murders of Susan Davis and Elizabeth Perry on Memorial Day 1969, a few weeks after the semester ended, is conspicuously absent from the story as well.

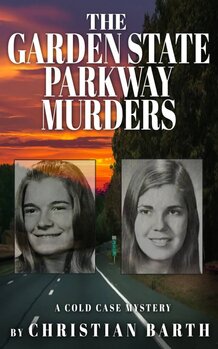

While gathering material for my forthcoming book, THE GARDEN STATE PARKWAY MURDERS: A COLD CASE MYSTERY, the first and only true account of the serial killer’s possible involvement in the Jersey Shore murders, I unearthed an entirely divergent narrative of Bundy’s origins, contradicting several commonly held assumptions. Each relative and Roxborough native I interviewed vehemently denied that Ted was abused as a young boy, or that his atrocities were at all attributable to his grandfather’s purported violent disposition and tyrannical hold upon his family. Though somewhat eccentric, Sam Cowell was a teetotaling, well-regarded horticulturist and doting grandfather, they insisted, not a “violent alcoholic” who “swung cats by the tail” and “once threw one of his daughters down the stairs when she missed curfew,” myriad journalists and authors have written time and time again, as if reporting an uncontroverted fact.

“He was a fine man,” said Sylvia Myers, a former member of the Roxborough Garden Club, recalling one occasion as she stood outside Sam’s Ridge Avenue home, helping him wrap burlap around a set of young dogwoods as his toddler grandson stood watching beside his mother. As the name Ted Bundy grew more infamous each year the body toll rose, Myers and her Roxborough neighborhood friends remained unable to reconcile the image of this serial killer with the little boy they saw scampering about his grandfather’s yard. And while their idyllic image of Bundy tarnished once they learned the grisly details of his horrific crimes, their views regarding Samuel Cowell haven’t wavered. They insist he was an upstanding citizen unfairly maligned due to his grandson’s name.

“The characterization that [Sam] was a raging alcoholic and animal abuser was a convenient characterization used to make people justify why Ted was the way he was,” Bundy’s cousin told me. “From my limited exposure to him, nothing could be farther from the truth. His daughters loved him dearly and had nothing but fond memories of him.”

For a far deeper exploration of Ted Bundy’s Philadelphia roots and his possible involvement in the 1969 Memorial Day slayings, make certain to read THE GARDEN STATE PARKWAY MURDERS, from WildBlue Press, available from Amazon beginning January 21, 2020.

Why was Ted Bundy so murderous? You will find the answer in chapter 12 of Erich Fromm’s masterpiece “The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness”, first published in 1973. Bundy’s diagnosis and the cause of it are the same as Hitler’s: Necrophilia caused by a malignant incestuous fixation on the mother. The mother was the problem, not the father. Hitler also had a sadistic father, but Fromm was not aware of it at the time his work was published. The first volume of Ian Kershaw’s biography of Hitler was published in 1998. In it the great historian describes how Hitler was severely beaten by his tyrannical father. Erich Fromm obviously had no access to this research. But for the development of the necrophile character, it’s the mother whose responsible, not the father, in Hitler’s and Bundy’s case.

Here are a few quotes from Fromm’s book: “I am speaking of children in whom no affective bonds toward mother emerge to break through the shell of autistic self-sufficiency. […] These children never break out of the shell of their narcissism: they never experience the mother as a love object; they never form any affective attachment to others, but, rather, look through them as if they were inanimate objects, and they often show a particular interest in mechanical things. […] It would seem that such infants never develop warm, erotic, and later, sexual feelings toward mother, or that they ever have a desire to be near her. Nor do they later fall in love with mother substitutes. For them mother is a symbol: a phantom rather than a real person. […] she is not the life-giving mother, but the death-giving mother; her embrace is death, her womb is a tomb. The attraction to the death-mother could not be affection or love; it is not an attraction in the common psychological sense denoting something pleasant and warm, but in the sense in which one would speak of magnetic attraction, or the attraction of gravity. The person tied to mother by malignant incestuous bonds remains narcissistic, cold, unresponsive; he is drawn to her as iron is drawn to a magnet; she is the ocean in which he wants to drown, the ground in which he wants to be buried. The reason for this development seems to be that the state of unmitigated narcissistic aloneness is intolerable; if there is no way of being related to mother or her substitute by warm, enjoyable bonds, the relatedness to her and to the whole world must become one of final union in death.”

Explaining the cause of Ted’s behavior vis-a-vis Fromm’s Anatomy of Human Destructiveness is pure psychobabble. If it were true, that Ted’s mother was the cause of his behavior, then surely her behavior is not unique. Many children were abandoned by their mothers in infancy – the large number of infants that are raised in orphanages etc, the infants left alone after birth at the Lund, for example, – if we take all these into account then the frequency of Ted-like characters in society ought to be much, much higher, when in fact, Ted-like characters are extremely rare. The sociological explanation for Ted-like sexual murderers completely fails.

The rejection of Erich Fromm speaks volumes about the sorry state of psychiatry and clinical psychology as they are taught today.

The love of death can express itself sexually or in other ways. It is not rare at all.

And do you believe most people who have necrophilous (or sadomasochistic) sexual fantasies usually go to psychotherapists and tell them about them? Many pedophiles never abuse children. Do you believe these people typically go to psychiatrists and tell them about their sexual preferences?

But let the great Erich Fromm speak for himself:

“This incestuous attraction to death, where it exists, is a passion in conflict with all other impulses fighting for the preservation of life. Hence it works in the dark and is usually entirely unconscious. The person with this malignant incestuousness will attempt to relate to people by less destructive bonds, such as sadistic control of others or the satisfaction of narcissism by gaining boundless admiration. If his life provides such relatively satisfactory solutions as success in work, prestige, etc., the destructiveness may never be expressed overtly in any major ways. If, on the other hand, he experiences failures, the malignant tendencies will come to the fore and the craving for destruction—of himself and others—will rule supreme.”

Fromm, Erich. The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (p. 404). Open Road Media. Kindle Edition.

How can children who were abandoned by their mothers develop a malignant incestuous fixation on their mothers? Neither Hitler nor Bundy were abandoned!